BURLINGTON, ON September 16, 2012 There are hundreds of people who took part in the Terry Fox run last Sunday who aren’t up to annual run but they nevertheless see this as an important annual event. Many have seen cancer threaten their families, others have lost members of their families or friends to the disease. The occasion for them is an opportunity to reflect and remember and pray for those fighting the disease. They want too, to contribute to the research and help find more of the root causes of cancer.

We’ve learned how damaging smoking was – but we didn’t know back in 1980 what we certainly know now about cigarette smoking – yet many of our youth still light up. We have work to do on the cancer research side as well as changing attitudes amongst some of our younger people.

On November 12, 1976, Terry Fox was driving home to Port Coquitlam, and became distracted by nearby bridge construction, and crashed into the back of a pickup truck. While his car was left a wreck that couldn’t be driven, Fox emerged with only a sore right knee.

He again felt pain in the knee a month later, but chose to ignore it until the end of basketball season. By March 1977, the pain had intensified and he finally went to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with osteosarcoma, a form of cancer that often starts near the knees. Fox believed his car accident weakened his knee and left it vulnerable to the disease, though his doctors argued there was no connection. He was told that his leg had to be amputated, he would require chemotherapy treatment, and that recent medical advances meant he had a 50 percent chance of survival. Fox learned that two years before the figure would have been only 15 percent; the improvement in survival rates impressed on him the value of cancer research.

With the help of an artificial leg, Fox was walking three weeks after the amputation. He then progressed to playing golf with his father. Doctors were impressed with Fox’s positive outlook, stating it contributed to his rapid recovery. He endured sixteen months of chemotherapy and found the time he spent in the British Columbia Cancer Control Agency facility difficult as he watched fellow cancer patients suffer and die from the disease. Fox ended his treatment with new purpose: he felt he owed his survival to medical advances and wished to live his life in a way that would help others find courage.

In the summer of 1977 Rick Hansen, working with the Canadian Wheelchair Sports Association, invited Fox to try out for his wheelchair basketball team. Although he was undergoing chemotherapy treatments at the time, Fox’s energy impressed Hansen. Less than two months after learning how to play the sport, Fox was named a member of the team for the national championship in Edmonton. He won three national titles with the team, and was named an all-star by the North American Wheelchair Basketball Association in 1980.

The night before his cancer surgery, Fox had been given an article about Dick Traum, the first amputee to complete the New York City Marathon. The article inspired him; he embarked on a 14-month training program, telling his family he planned to compete in a marathon himself. In private, he devised a more extensive plan. His hospital experiences had made Fox angry at how little money was dedicated to cancer research. He intended to run the length of Canada in the hope of increasing cancer awareness, a goal he initially only divulged to his friend Douglas Alward.

Fox ran with an unusual gait, as he was required to hop-step on his good leg due to the extra time the springs in his artificial leg required to reset after each step. He found the training painful as the additional pressure he had to place on both his good leg and his stump led to bone bruises, blisters and intense pain. Fox found that after about 20 minutes of each run, he crossed a pain threshold and the run became easier.

In August 1979, Fox competed in a marathon in Prince George, British Columbia. He finished in last place, ten minutes behind his closest competitor, but his effort was met with tears and applause from the other participants. Following the marathon, he revealed his full plan to his family. His mother discouraged him, angering Fox, though she later came to support the project. She recalled, “He said, ‘I thought you’d be one of the first persons to believe in me.’ And I wasn’t. I was the first person who let him down”. Fox initially hoped to raise $1 million, then $10 million, but later sought to raise $1 for each of Canada’s 24 million people.

On October 15, 1979, Fox sent a letter to the Canadian Cancer Society in which he announced his goal and appealed for funding. He stated that he would “conquer” his disability, and promised to complete his run, even if he had to “crawl every last mile”. Explaining why he wanted to raise money for research, Fox described his personal experience of cancer treatment, Fox said: “soon realized that that would only be half my quest, for as I went through the 16 months of the physically and emotionally draining ordeal of chemotherapy, I was rudely awakened by the feelings that surrounded and coursed through the cancer clinic. There were faces with the brave smiles, and the ones who had given up smiling. There were feelings of hopeful denial, and the feelings of despair. My quest would not be a selfish one. I could not leave knowing these faces and feelings would still exist, even though I would be set free from mine. Somewhere the hurting must stop….and I was determined to take myself to the limit for this cause”.

Fox made no promises that his efforts would lead to a cure for cancer, but he closed his letter with the statement: “We need your help. The people in cancer clinics all over the world need people who believe in miracles. I am not a dreamer, and I am not saying that this will initiate any kind of definitive answer or cure to cancer. I believe in miracles. I have to.”

The Cancer Society was skeptical of his dedication, but agreed to support Fox once he had acquired sponsors and requested he get a medical certificate from a heart specialist stating that he was fit to attempt the run. Fox was diagnosed with left ventricular hypertrophy — an enlarged heart — a condition commonly associated with athletes. Doctors warned Fox of the potential risks he faced, though they did not consider his condition a significant concern. They endorsed his participation when he promised that he would stop immediately if he began to experience any heart problems.

A second letter was sent to several corporations seeking donations for a vehicle, running shoes and to cover the other costs of the run. Fox sent other letters asking for grants to buy a running leg. He observed that while he was grateful to be alive following his cancer treatment, “I remember promising myself that, should I live, I would rise up to meet this new challenge of fundraising for cancer research face to face and prove myself worthy of life, something too many people take for granted.”

The Ford Motor Company donated a camper van, while Imperial Oil contributed fuel, and Adidas his running shoes. Fox turned away any company that requested he endorse their products and refused any donation that carried conditions as he insisted that nobody was to profit from his run.

The Marathon began on April 12, 1980, when Fox dipped his right leg in the Atlantic Ocean near St. John’s, Newfoundland, and filled two large bottles with ocean water. He intended to keep one as a souvenir and pour the other into the Pacific Ocean upon completing his journey at Victoria, British Columbia. Fox was supported on his run by Doug Alward, who drove the van and cooked meals.

It was at about this time that Don Pace heard the story and knew there had to be a Terry Fox run in Burlington. He organized the 1981 and 1982 events and was the official starter for the races last weekend.

Fox was met with gale force winds, heavy rain and a snowstorm in the first days of his run. He was initially disappointed with the reception he received, but was heartened upon arriving in Port aux Basques, Newfoundland, where the town’s 10,000 residents presented him with a donation of over $10,000. Throughout the trip, Fox frequently expressed his anger and frustration to those he saw as impeding the run, and he fought regularly with Alward. By the time they reached Nova Scotia, they were barely on speaking terms, and it was arranged for Fox’s brother Darrell, then 17, to join them as a buffer.

Determination and grit got this woman over the finish line. It was the same story for hundreds of both walkers and runners. Deb Tymstra on the right calling the runners in.

Fox left the Maritimes on June 10 and faced new challenges entering Quebec due to his group’s inability to speak French and drivers who continually forced him off the road. Fox arrived in Montreal on June 22, one-third of the way through his 8,000-kilometre (5,000 mi) journey, having collected over $200,000 in donations. Around this time, Terry Fox’s run caught the attention of Isadore Sharp who was the founder and CEO of Four Seasons Hotel and Resorts—and who had lost a son to melanoma in 1978 just a year after Terry’s diagnosis. Sharp was intrigued by the story of a one-legged kid “trying to do the impossible” and run across the country; so he offered food and accommodation at his hotels en route. When Terry was discouraged because so few people were making donations, Sharp pledged $2 a mile to the run and persuaded close to 1,000 other corporations to do the same. Sharp’s encouragement persuaded Terry to continue with the Marathon of Hope. Convinced by the Canadian Cancer Society that arriving in Ottawa for Canada Day would aid fundraising efforts, he remained in Montreal for a few extra days.

Fox crossed into Ontario at the town of Hawkesbury on the last Saturday in June. He was met by a brass band and thousands of residents who lined the streets to cheer him on, while the Ontario Provincial Police gave him an escort throughout the province. Despite the sweltering heat of summer, he continued to run 26 miles (42 km) per day. On his arrival in Ottawa, Fox met Governor General Ed Schreyer and Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau and was the guest of honour at numerous sporting events in the city. In front of 16,000 fans, he performed a ceremonial kickoff at a Canadian Football League game and was given a standing ovation. Fox’s journal reflected his growing excitement at the reception he had received as he began to understand how deeply moved Canadians were by his efforts.

A crowd of 10,000 people met Fox in Toronto, where he was honoured in Nathan Phillips Square. As he ran to the square, he was joined on the road by many people, including National Hockey League star Darryl Sittler, who presented Fox with his 1980 All-Star Game jersey. The Cancer Society estimated it collected $100,000 in donations that day alone. As he continued through southern Ontario, he was met by Hockey Hall of Famer Bobby Orr who presented him with a cheque for $25,000. Fox considered meeting Orr the highlight of his journey.

This guy was going to make it – without any help from his Mother. Two younger runners come up the rear racing for the finish line.

“Everybody seems to have given up hope of trying. I haven’t. It isn’t easy and it isn’t supposed to be, but I’m accomplishing something. How many people give up a lot to do something good. I’m sure we would have found a cure for cancer 20 years ago if we had really tried”

As Fox’s fame grew, the Cancer Society scheduled him to attend more functions and give more speeches. Fox attempted to accommodate any request that he believed would raise money, no matter how far out of his way it took him. He bristled, however, at what he felt were media intrusions into his personal life, for example when the Toronto Star reported that he had gone on a date. Fox was left unsure whom he could trust in the media after negative articles began to emerge, including one by the Globe and Mail that characterized him as a “tyrannical brother” who verbally abused Darrell and claimed he was running because he held a grudge against a doctor who had misdiagnosed his condition, allegations he referred to as “trash”.

The physical demands of running a marathon every day took its toll on Fox’s body. Apart from the rest days in Montreal taken at the request of the Cancer Society, he refused to take a day off, even on his 22nd birthday. He frequently suffered shin splints and an inflamed knee. He developed cysts on his stump and experienced dizzy spells. At one point, he suffered a soreness in his ankle that would not go away. Although he feared he had developed a stress fracture, he ran for three more days before seeking medical attention, and was then relieved to learn it was tendonitis and could be treated with painkillers. Fox rejected calls for him to seek regular medical checkups, and dismissed suggestions he was risking his future health.

In spite of his immense recuperative capacity, Fox found that by late August he was exhausted before he began his day’s run. On September 1, outside of Thunder Bay, he was forced to stop briefly after he suffered an intense coughing fit and experienced pains in his chest. Unsure what to do, he resumed running as the crowds along the highway shouted out their encouragement. A few miles later, short of breath and with continued chest pain, he asked Alward to drive him to a hospital. He feared immediately that he had run his last kilometer. The next day, Fox held a tearful press conference during which he announced that his cancer had returned and spread to his lungs. He was forced to end his run after 143 days and 5,373 kilometres (3,339 mi). Fox refused offers to complete the run in his stead, stating that he wanted to complete his marathon himself.

Fox had raised $1.7 million by the time he was forced to abandon the Marathon. He realized that the nation was about to see the consequences of the disease, and hoped that this might lead to greater generosity. A week after his run ended, the CTV Television Network organized a nationwide telethon in support of Fox and the Canadian Cancer Society. Supported by Canadian and international celebrities, the five-hour event raised $10.5 million. Among the donations were $1 million each by the governments of British Columbia and Ontario, the former to create a new research institute to be founded in Fox’s name, and the latter an endowment given to the Ontario Cancer Treatment and Research Foundation. Donations continued throughout the winter, and by the following April, over $23 million had been raised.

Supporters and well wishers from around the world inundated Fox with letters and tokens of support. At one point, he was receiving more mail than the rest of Port Coquitlam combined. Such was his fame that one letter addressed simply to “Terry Fox, Canada” was successfully delivered.

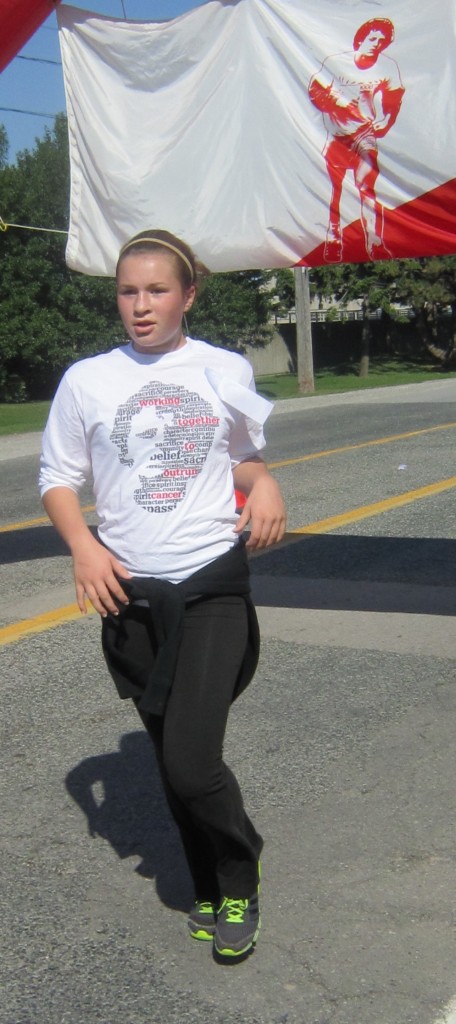

Young girl beats her Dad in the home stretch of the Burlington 2012 Terry Fox Run for cancer research

In September 1980 he was invested in a special ceremony as a Companion of the Order of Canada; he was the youngest person to be so honoured. The Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia named him to the Order of the Dogwood, the province’s highest award. Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame commissioned a permanent exhibit, and Fox was named the winner of the Lou Marsh Award for 1980 as the nation’s top athlete. He was named Canada’s 1980 Newsmaker of the Year. The Ottawa Citizen described the national response to his marathon as “one of the most powerful outpourings of emotion and generosity in Canada’s history”.

Each of these woman had their own reasons for running this race and each ran it in their own way. Hundreds did just this during the Terry Fox Run for cancer research

In the following months, Fox received multiple chemotherapy treatments; however, the disease continued to spread. As his condition worsened, Canadians hoped for a miracle and Pope John Paul II sent a telegram saying that he was praying for Fox. Doctors turned to experimental interferon treatments, though their effectiveness against osteogenic sarcoma was unknown. He suffered an adverse reaction to his first treatment, but continued the program after a period of rest.

Fox was re-admitted to the Royal Columbian Hospital in New Westminster on June 19, 1981, with chest congestion and developed pneumonia. He fell into a coma and died at 4:35 a.m. PDT on June 28, 1981, with his family by his side. The Government of Canada ordered flags across the country lowered to half-staff, an unprecedented honour that was usually reserved for statesmen. Addressing the House of Commons, Trudeau said, “It occurs very rarely in the life of a nation that the courageous spirit of one person unites all people in the celebration of his life and in the mourning of his death … We do not think of him as one who was defeated by misfortune but as one who inspired us with the example of the triumph of the human spirit over adversity”.

His funeral, was broadcast on national television; hundreds of communities across Canada also held memorial services, a public memorial service was held on Parliament Hill in Ottawa, and Canadians again overwhelmed Cancer Society offices with donations.

Fox remains a prominent figure in Canadian folklore. His determination united the nation; people from all walks of life lent their support to his run and his memory inspires pride in all regions of the country. A 1999 national survey named him as Canada’s greatest hero, and he finished second to Tommy Douglas in the 2004 Canadian Broadcasting Corporation program The Greatest Canadian. Fox’s heroic status has been attributed to his image as an ordinary person attempting a remarkable and inspirational feat. Others have argued that Fox’s greatness derives from his audacious vision, his determined pursuit of his goal, his ability to overcome challenges such as his lack of experience and the very loneliness of his venture. As Fox’s advocate on The Greatest Canadian, media personality Sook-Yin Lee compared him to a classic hero, Phidippides, the runner who delivered the news of the Battle of Marathon before dying, and asserted that Fox “embodies the most cherished Canadian values: compassion, commitment, perseverance”. She highlighted the juxtaposition between his celebrity, brought about by the unforgettable image he created, and his rejection of the trappings of that celebrity.

Part 1 of a 4 part photo essay.

Part 2 of a 4 part photo essay.